Chapter 4: The Aftermath

Listen to Kodiak residents describe what they saw and how they felt the day after the earthquake. Hear them describe what those first weeks were like in Kodiak after the tsunami.

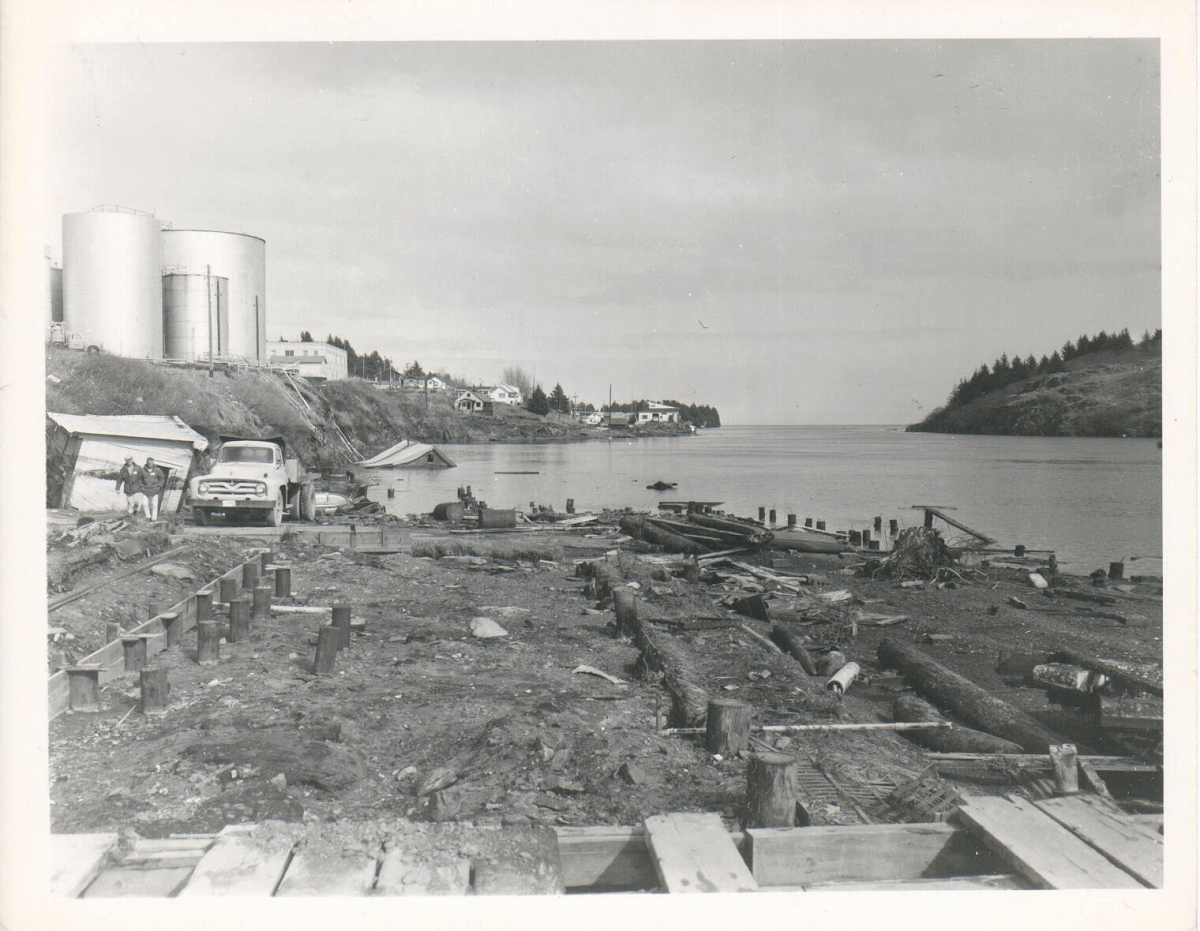

The morning after the earthquake, Kodiak residents woke to find their hometown nearly unrecognizable. Canneries, warehouses, and seaplane docking along the waterfront had disappeared. The entire boat harbor, too, was gone. Heaps of rubble lay where bars, banks, stores, and houses had stood the day before. Diesel fuel from tanks that heated downtown buildings now drenched the wreckage and filled the air with fumes.

Looking north down the Near Island Channel, exposed piling is all that remains of the warehouses, docks, boats, and the McConaghy’s Cannery built in the channel where the ferry dock at the end of Center Avenue now is located.

Leif J. Norman photo courtesy of Nancy Norman Sweeney

“The roads were all torn up, muddy, miserable. There were huge trucks from the reconstruction crews running back and forth. I thought for sure kids were going to get killed. But we lucked out.” ~ Betty Springhill

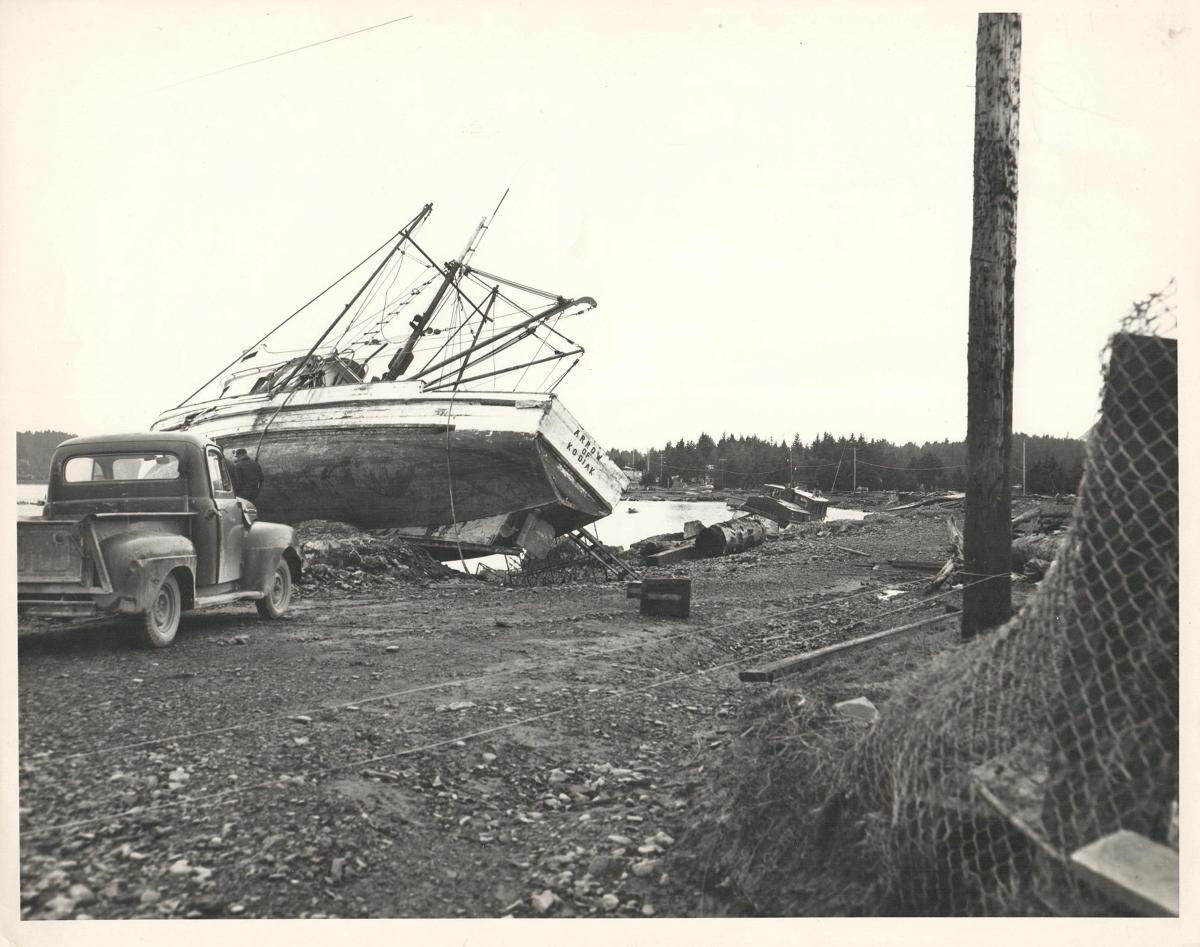

Amidst it all, boats lay on their sides like dead fish. The 90-foot F/V Selief, with its fish holds full of rotting, stinking king crab, stood high and dry like a gravestone marking old Kodiak. One of the top fishing ports in the nation at the peak of a multi-million dollar king crab boom, Kodiak was now at a standstill.

A fisherman inspects the hull of the F/V Arrow of Kodiak three days after the tsunami left it high and dry on Mission Beach.

Leif J. Norman photo, March 30, 1964, courtesy of Nancy Norman Sweeney

“I felt like everything [was] over with. There won’t be any future for this place … Everything was like at a standstill. And it was. It seemed like everybody was stunned.” ~ Art Zimmer

For the next several days power was out and phone service was down, leaving Kodiak residents cut off from family and friends Outside. When the media first reported that Kodiak Island had sunk, distant loved ones despaired, thinking the entire island had vanished along with their families and friends.

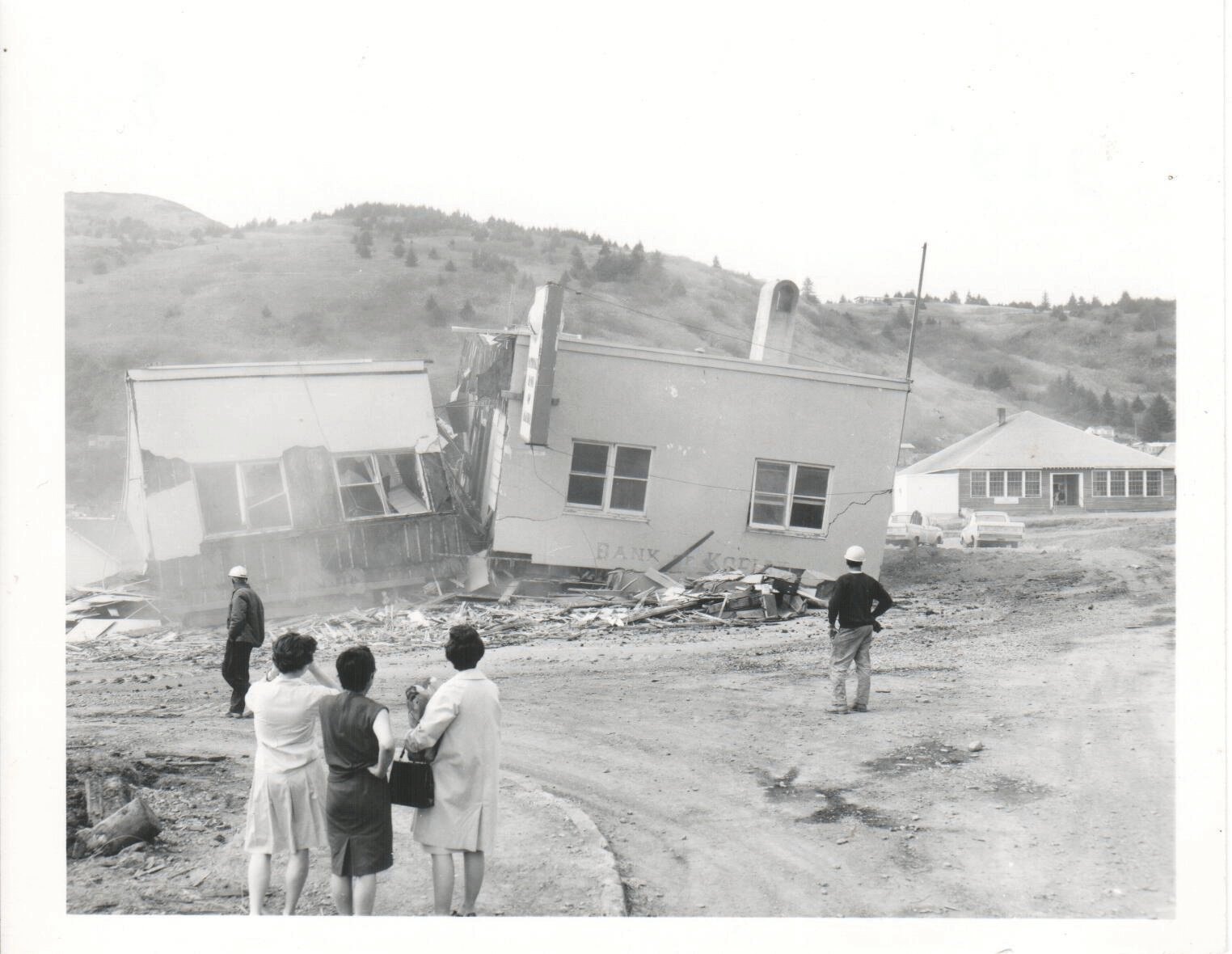

Onlookers watch the Bank of Kodiak, center, come down to make way for rebuilding downtown Kodiak with federal Urban Renewal low-interest funding. The schoolhouse to the right also was removed during urban renewal.

Leif J. Norman photo courtesy of Nancy Norman Sweeney

Read the letter Georgia Norman wrote to her daughter and son-in-law, Nancy and Tom Sweeney, three days after the earthquake. In the letter she tells how she and her husband, Leif, narrowly escaped the tsunami. She goes on to describe the level of devastation and the loss they suffered after the tsunami destroyed Norman’s Photo Shop, their store and home in downtown Kodiak.

“The tidal wave destroyed everything including the brand new parking meters the city had just put in that we haven’t had since.” ~ Candy McGuire

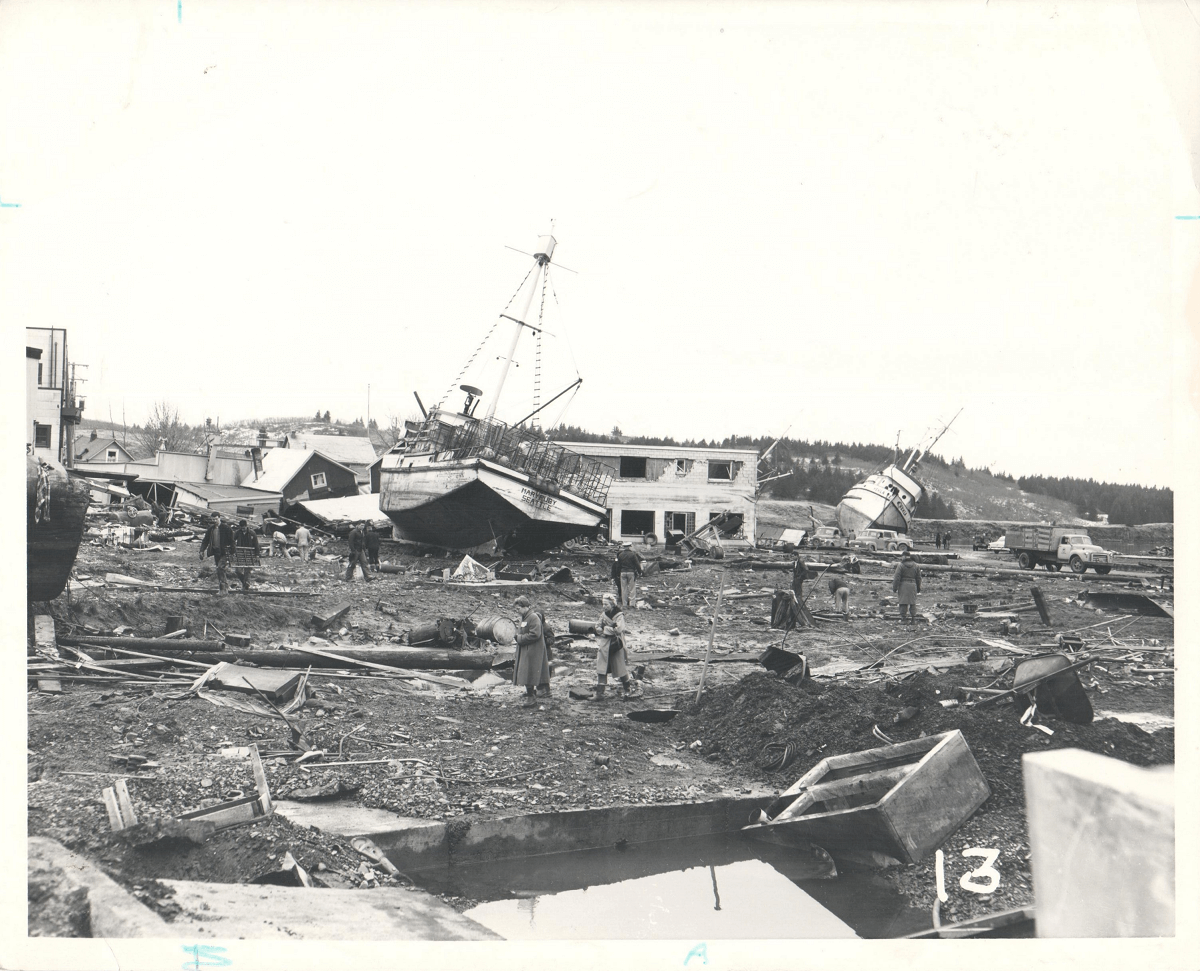

In town, word spread about friends and family found alive and those lost in the tsunami. Among those lost were fishermen aboard the F/V Spruce Cape trying to make it home to their families in Ouzinkie, picnickers heading back to town along the Chiniak Highway, Kaguyak residents failing to escape the tsunami that destroyed their village, a woman and a young girl asleep on a boat in the harbor, a hospital patient who suffered heart failure in the high school emergency shelter.

The fishing vessel Mary Ruby, with crab pots still tied to her back deck, and the Hekla lay on their sides as residents pick through the wreckage of downtown Kodiak in hopes of salvaging some of their belongings.

Leif J. Norman photo, March 30, 1964, courtesy of Nancy Norman Sweeney